The Impact of LWCF

Don’t let the Land and Water Conservation Fund disappear. Though the LWCF has cost the Montana taxpayer $0 in the 54 years since it was passed, 84% of the program could be cut this year.

Land and Water Conservation Fund Brings Local Conservation to Life

In conservation, the Land and Water Conservation Fund is big. Each year, energy companies pay big royalties out of the profits they earn from off-shore drilling. These royalties go into a big national fund, and big heads-of-state mull over how much is actually allowed to go to public land and water projects. The impacts of these decisions are big, especially in Montana, where we not only recreate at the hundreds of ballparks, playgrounds, fishing access sites and historical locations sponsored by the LWCF, we depend on the income generated from our working forests and agricultural lands – industries supported directly and indirectly by LWCF funds.

Rather than getting lost in the big budgets and stats, however, we thought it beneficial to instead look at the local impacts and show just a couple of ways LWCF has improved our small Montana community. In Prickly Pear Land Trusts’ short lifetime, we have already tapped the LWCF program twice to support key, community-driven conservation projects. Each of the projects described below carries a unique public value, but both highlight the type of work and victories for public lands and access that the LWCF enables.

Democracy in Practice – Spring Hill Becomes Wakina Sky

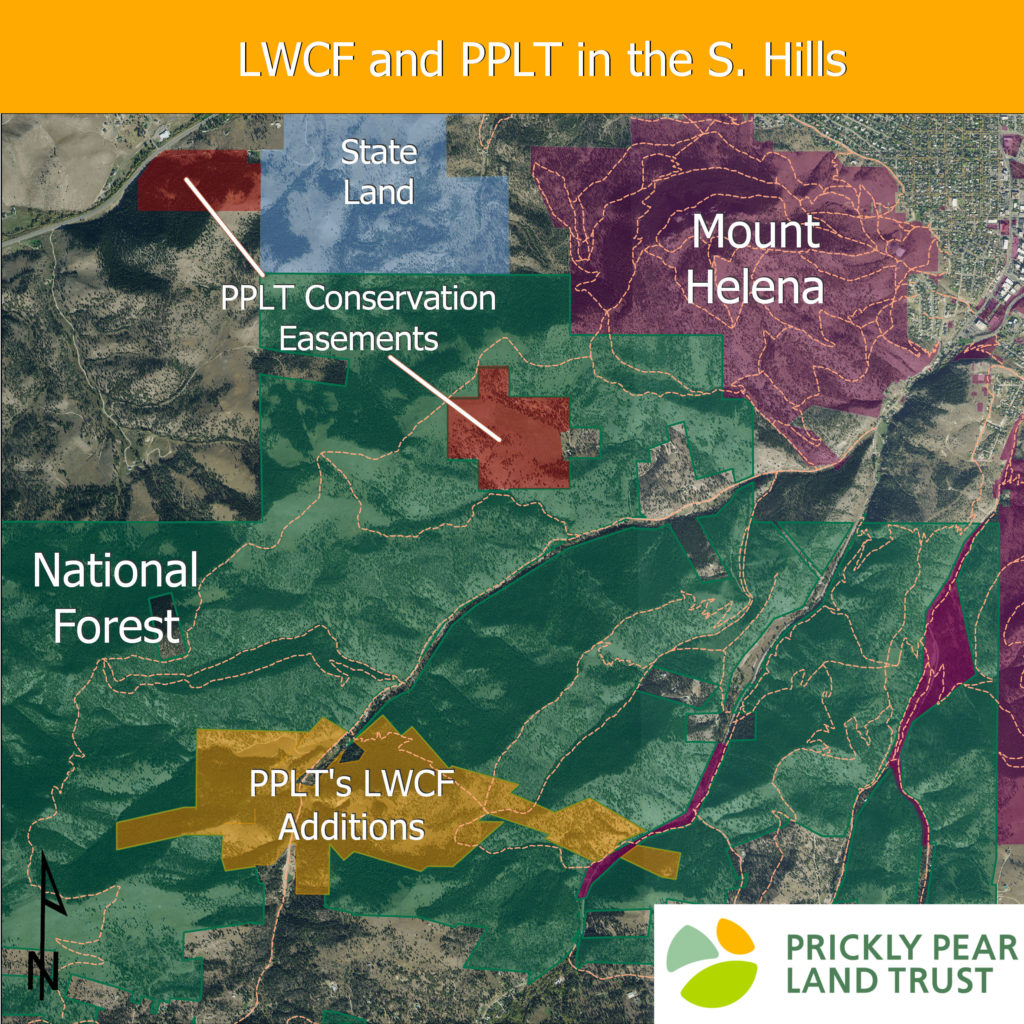

As Helena’s historic Park Avenue winds southward and the bar and restaurant scene gives way to restored miner’s shacks and crumbling wells, the road is suddenly split into Oro Fino Gulch and its gravelly counterpart, Grizzly Gulch. The wedge between these gradually broadens to become the mile-wide, Wakina Sky portion of the South Hills trail system. While the trails that crisscross Wakina’s slopes see fewer users than neighboring Mount Helena and Mount Ascension, Wakina Sky rewards its guests with a more backcountry feel. Its remoteness and views are the draw.

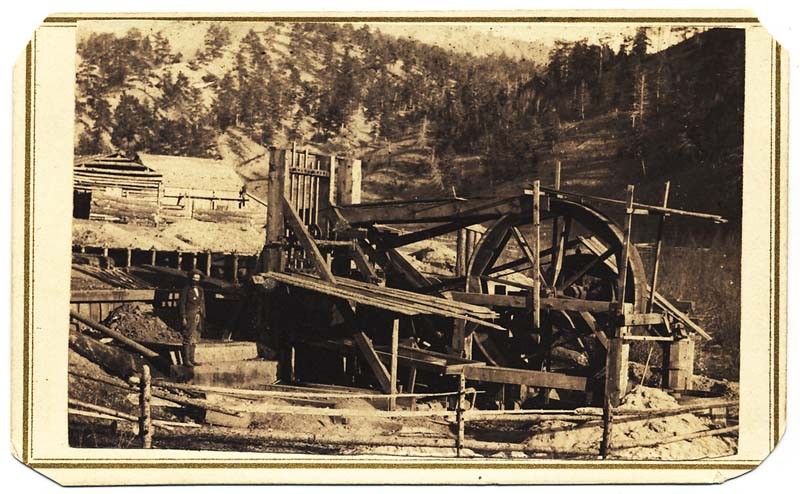

Now a permanent fixture in the Helena National Forest, a large section of what is Wakina Sky was at one point anything but secure. The southernmost end of Wakina Sky was for over a century a part of the Spring Hill mining block. The Spring Hill Mine was active for decades and at its height in the late 1800s, was only out-produced by the Anaconda Company in Butte. After a 1999 hazmat cleanup by the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), the owners of the defunct mine, Ardic Exploration and Development, Inc. offered to sell the entire property for public use, but the offer only extended about a year. If PPLT and its partners did not act, the property would be placed on the real estate market and likely developed.

Now a permanent fixture in the Helena National Forest, a large section of what is Wakina Sky was at one point anything but secure. The southernmost end of Wakina Sky was for over a century a part of the Spring Hill mining block. The Spring Hill Mine was active for decades and at its height in the late 1800s, was only out-produced by the Anaconda Company in Butte. After a 1999 hazmat cleanup by the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), the owners of the defunct mine, Ardic Exploration and Development, Inc. offered to sell the entire property for public use, but the offer only extended about a year. If PPLT and its partners did not act, the property would be placed on the real estate market and likely developed.

Roughly 457 acres in size, the Spring Hill property spanned over two miles, spilling across Oro Fino and Grizzly Gulches into the Waterline and Mount Helena Ridge areas. The entire property consisted of 26 contiguous mining claims, making subdivision not only an attractive option, but a streamlined one.

Given the opportunity to save the property from this fate and preserve it for Montana’s public, PPLT decided to pursue the ambitious project. As a private nonprofit, PPLT was in a unique position to quickly acquire the property, raise the funds for purchase, and give the Forest Service time to get the property approved for inclusion within the Helena National Forest. Egged on by its supporters and a community hell-bent on protecting access, habitat, and history, PPLT put together a strategy for the purchase. Locally based Mountain West Bank saw the project as a worthwhile investment and provided a bridge loan for PPLT to acquire the property.

In 2003, PPLT purchased the Spring Hill block. The down payment for the loan was financed through the nearly $50,000 in private donations received by PPLT. Seeing the obvious public value of the project, the Montana Discovery Foundation and Montana Fish and Wildlife Conservation Trust jumped at the chance to support the purchase, providing $150,000. The Montana History Foundation provided support as well, through a clever land swap. To finalize the project and transfer the property safely to Helena National Forest, PPLT still needed over half a million dollars to pay the principle and final interest of the loan. Without this significant sum, PPLT risked diverting significant funds from other projects and trail maintenance, or worse, defaulting on the loan. In 2006, the Land and Water Conservation Fund request for $600,000 was approved, completing PPLT’s debt obligation and creating over 400 prime acres of community and wildlife space for Montanans. Now, instead of a fractured landscape, we have the intersection of the Goat Trail, Barking Dog, Wakina Sky, and Stairway to Heaven, as well as prime habitat for elk, deer, and moose.

The LWCF-Spring Hill project is a case study for how democracy in modern America can still work for the benefit of the public and the environment. The project moved forward due to proactive members of the community and cooperative partnerships between public and private entities. Besides the important services provided by Mountain West Bank, PPLT’s conservation partners and state and federal agencies, the project was backed by over 200 smaller donations, from businesses and residents around the Helena Valley ranging anywhere from five, ten, and twenty dollars, to hundreds and thousands of dollars. The Forest Service and Senator Conrad Burns are also notable for their roles as facilitators. In his capacity as a member of the Interior Appropriations Sub-committee, Burns enthusiastically endorsed the acquisition, noting that the LWCF and public funds were designed for just this type of community-led project.

The LWCF-Spring Hill project is a case study for how democracy in modern America can still work for the benefit of the public and the environment. The project moved forward due to proactive members of the community and cooperative partnerships between public and private entities. Besides the important services provided by Mountain West Bank, PPLT’s conservation partners and state and federal agencies, the project was backed by over 200 smaller donations, from businesses and residents around the Helena Valley ranging anywhere from five, ten, and twenty dollars, to hundreds and thousands of dollars. The Forest Service and Senator Conrad Burns are also notable for their roles as facilitators. In his capacity as a member of the Interior Appropriations Sub-committee, Burns enthusiastically endorsed the acquisition, noting that the LWCF and public funds were designed for just this type of community-led project.

Creativity in Conservation – Cooperation Makes York Gulch Recreation a Reality

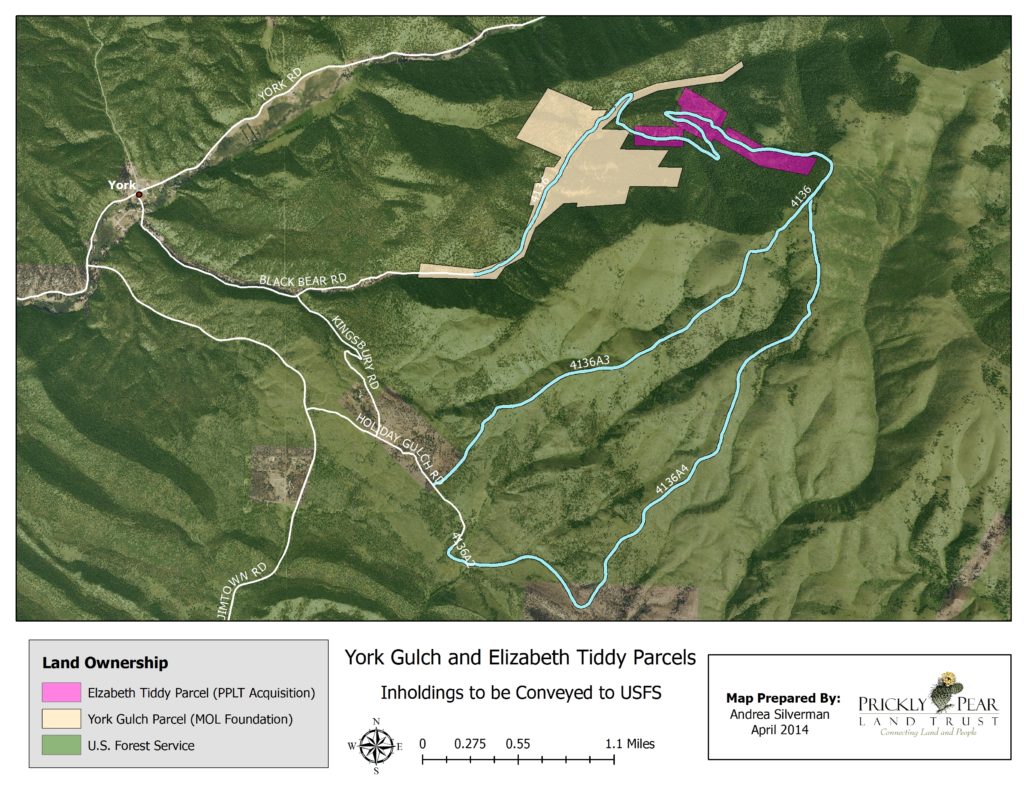

A decade after the Spring Hill success, PPLT helped orchestrate a similar, but more complex, project just outside the mountain community of York, Montana. While the Spring Hill project took place in Helena’s South Hills, the York Gulch project is tucked up a forested draw in the dramatic, cliff-riddled segment of the Big Belts that abuts the eastern edge of Hauser Lake. An area ripe with ecological value, the Belts provide a stellar corridor for elk deer, bear, moose, turkeys, mountain lions, lynx, pine marten; even some wolverine, wolves and grizzlies have been spotted.

A short distance from town, the York Gulch project area had been the site of mining activity as well, hosting nineteen contiguous claims active during the mid-1800s. By the 2000s, the inholdings, occupying a picturesque entry point to the 360 degrees of national forest, had consolidated into just two ownerships.

Five of the claims, encompassing about 100 acres, were owned for more than 30 years by Mrs. Betty Tiddy and her late husband. Mrs. Tiddy, understanding full well the conservation and recreational value of her property, had conveyed her interest in selling to the various public land groups and PPLT.

Five of the claims, encompassing about 100 acres, were owned for more than 30 years by Mrs. Betty Tiddy and her late husband. Mrs. Tiddy, understanding full well the conservation and recreational value of her property, had conveyed her interest in selling to the various public land groups and PPLT.

The second property, 286 acres owned by the conservation organization Montana’s Outdoor Legacy Foundation, had been acquired after DEQ had addressed the health and environmental challenges inherited from mining in 2009. Mrs. Tiddy’s conservation bent was incredibly fortunate because securing her property, substantial in size and equally serene, meant that it and the Outdoor Legacy property could connect the entirety of the Gulch. For land planners perpetually looking at the checker-boarded, piecemeal property ownership map, projects like York Gulch are a diamond in the rough. Rarely do you find two substantial properties, in size, ecological value, and public worth, next to one another, with willing landowners, and completely surrounded by protected lands. The question was not whether we do it, but how.

The largest obstacles in this particular project were instead a) the cost, and, b) prepping the Tiddy property for public access prior to the transfer of the combined Outdoor Legacy and Tiddy lands to the Forest Service. Building on the past successes of partnerships, Montana’s Outdoor Legacy Foundation, the Forest Service, and PPLT brought every conservation partner they could find to the table. In a similar fashion to the Spring Hill project, the partners agreed that PPLT was again in the position to be an intermediary holder of the Tiddy property. Outdoor Legacy was already holding and managing its 286 acres in this way. With partners in place, the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, stepped up to the plate, covering the cost of the appraisal. Once these numbers were established, PPLT and company could again begin to cobble together a funding package to cover the nearly $1 million price of the combined properties. The Montana Fish and Wildlife Conservation Trust, a financial supporter from the Spring Hill project era, threw its weight behind the project, kicking in the majority of funds needed for the Tiddy purchase as well as contributing to the pot for the eventual purchase of the Outdoor Legacy portion. To procure the Tiddy property, PPLT leveraged the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Trust funds to secure a bridge loan from The Conservation Fund, essentially a D.C.-based bank for conservation. And in February of 2013, PPLT purchased the 100 acres that otherwise would have separated the public from access to York Gulch.

The largest obstacles in this particular project were instead a) the cost, and, b) prepping the Tiddy property for public access prior to the transfer of the combined Outdoor Legacy and Tiddy lands to the Forest Service. Building on the past successes of partnerships, Montana’s Outdoor Legacy Foundation, the Forest Service, and PPLT brought every conservation partner they could find to the table. In a similar fashion to the Spring Hill project, the partners agreed that PPLT was again in the position to be an intermediary holder of the Tiddy property. Outdoor Legacy was already holding and managing its 286 acres in this way. With partners in place, the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, stepped up to the plate, covering the cost of the appraisal. Once these numbers were established, PPLT and company could again begin to cobble together a funding package to cover the nearly $1 million price of the combined properties. The Montana Fish and Wildlife Conservation Trust, a financial supporter from the Spring Hill project era, threw its weight behind the project, kicking in the majority of funds needed for the Tiddy purchase as well as contributing to the pot for the eventual purchase of the Outdoor Legacy portion. To procure the Tiddy property, PPLT leveraged the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Trust funds to secure a bridge loan from The Conservation Fund, essentially a D.C.-based bank for conservation. And in February of 2013, PPLT purchased the 100 acres that otherwise would have separated the public from access to York Gulch.

Completing the project at this point wasn’t as simple as finishing the purchases and handing over the property to the Helena National Forest. The York Gulch property, while already accessible via a private road, this access could be cut and the recreation area marooned without another access. Safeguarding access across Tiddy property first was a must. Once the properties were included in the National Forest, receiving a road easement would be costly in terms of time, money, and effort. Instead, while the properties were still in private hands, Fish, Wildlife, and Parks used $50,000 from its Public Access Fund to purchase a road easement. This ensured that when the Forest Service purchased the land, a road managed by the State of Montana would be included in the deed and guaranteed.

In the meantime, partnerships continued to bloom. While the Forest Supervisor for the Helena National Forest lobbied for LWCF funds, private and public funders joined in the project. Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and The Mule Deer Foundation each contributed $25,000 and vocal support for the project. The Board of Commissioners of Lewis and Clark County joined in the chorus as well, unanimously voting to sponsor the project with $205,000 of Open Space Bond funding. The commissioners followed up the contribution with a letter of support for the LWCF application, highlighting the high level of public support and value generated from the project. In 2014, the amount of $324,700 was appropriated through the LWCF for the Helena National Forest to purchase the properties.

In the meantime, partnerships continued to bloom. While the Forest Supervisor for the Helena National Forest lobbied for LWCF funds, private and public funders joined in the project. Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and The Mule Deer Foundation each contributed $25,000 and vocal support for the project. The Board of Commissioners of Lewis and Clark County joined in the chorus as well, unanimously voting to sponsor the project with $205,000 of Open Space Bond funding. The commissioners followed up the contribution with a letter of support for the LWCF application, highlighting the high level of public support and value generated from the project. In 2014, the amount of $324,700 was appropriated through the LWCF for the Helena National Forest to purchase the properties.

Today, if you travel up York Gulch, you can hike, mountain bike, drive, or ride your horse or ATV through a beautiful and historic piece of Montana.

Local Works

The Land and Water Conservation Fund is a big deal. LWCF projects like these are everywhere. With LWCF support, local organizations across Montana are working to keep Montana open, wild, fun, functional, and available to all. Without the LWCF, we would have an obvious and jarring gap in our trails. Without LWCF, the path for recreationists to York Gulch and Hedges Mountain would be blocked. But in looking at these examples, we see that the LWCF does more than just pay recreation and conservation bills, it enables communities to choose conservation for themselves. The LWCF does not stand alone, it rewards the communities with skin in the game and enables public and private individuals to do the right thing for their communities.

We encourage anyone who enjoys the outdoors in any capacity to look just a little deeper at the variety of projects and places where LWCF is at work. How did those soccer fields get built? Where does the money come from for parking at your favorite fishing hole? Was the land you run on or the trail where your kids learned to bike always public? The LWCF depends on public support to be reinstated and fully funded. Support the local and keep LWCF big.